Leak on Data Retention: What are the EU Governments planning for 2023?

At the end of November 2022, the »Working Party on Cooperation in Criminal Matters (COPEN)« of the Council of the European Union met for an informal video conference. They discussed i.a. the retention of citizens’ communication data and other surveillance-related issues. Now German investigative journalist Andre Meister has published the documents (Mastodon/Twitter). In addition to the protocol of the meeting, the documents contain presentations by Belgium, Germany, Ireland and Portugal on the recent rulings of the EU Court of Justice and on national legislation.

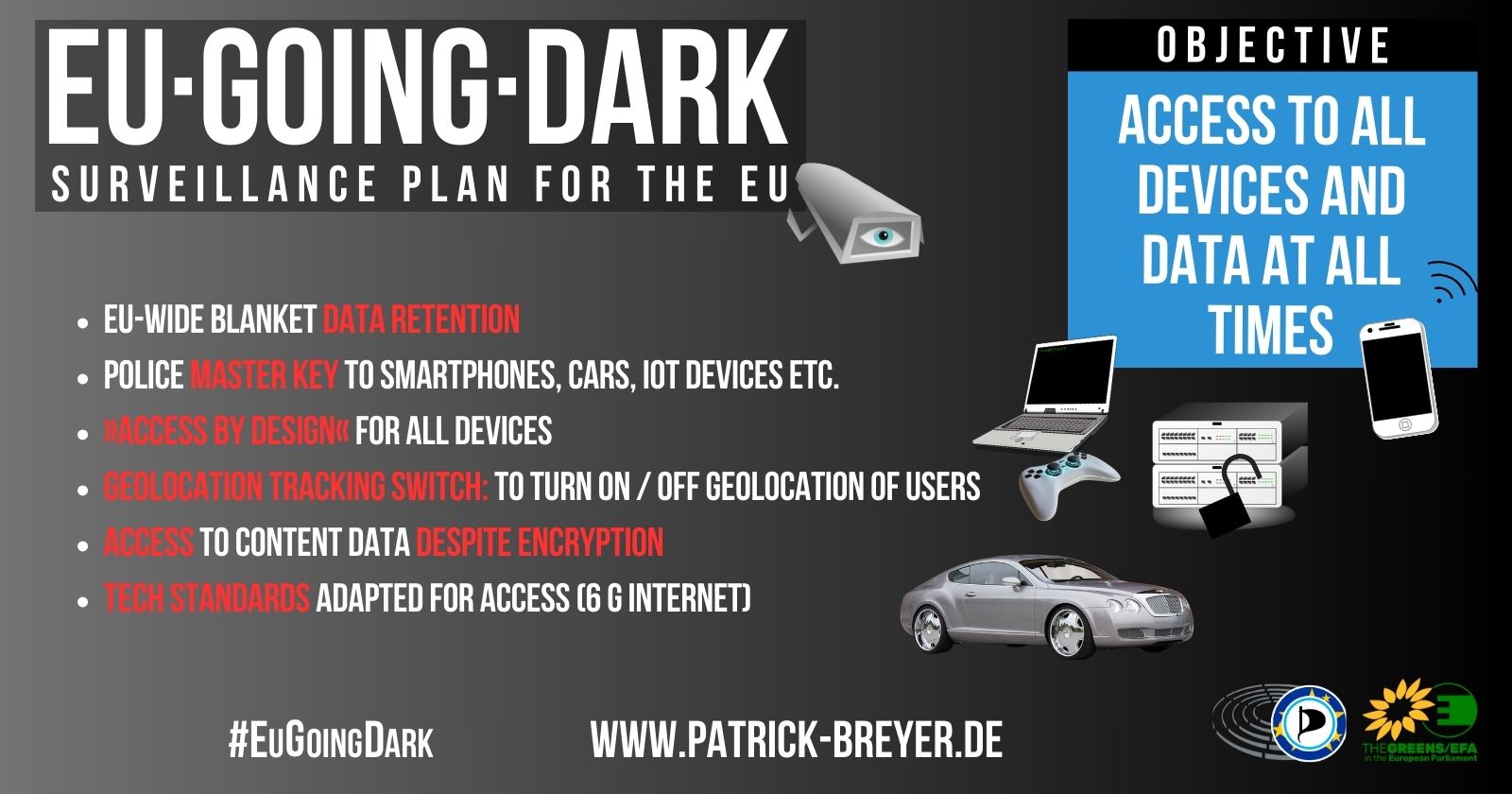

Member of the European Parliament Patrick Breyer (Pirate Party, Greens/EFA group) comments:

“The leaked documents prove that indiscriminate retention of the entire population’s contacts and movements in the European Union continues to be pushed in the Council of the European Union, contrary to numerous Court rulings. National bulk data retention legislation in most EU Member States is illegal , including attempts to justify it with a ‘permanent state of emergency’ in France and Denmark, or with regional crime rates in Belgium. The bulk collection of information on the everyday communications and movements of millions of unsuspected people constitutes an unprecedented attack on our right to privacy and is the most invasive method of mass surveillance directed against the state’s own citizens. Mass surveillance is the opposite of what European values embody. The Commission now finally needs to end impunity and start enforcing our right to privacy throughout Europe!

The anecdotal results of data retention policies are nowhere close to the damage the chilling effect of this surveillance weapon inflicts on our societies, as a recent survey found. Data retention laws have no measurable effect on the crime rate or the crime clearance rate in any EU country. Requests for communications data are rarely unsuccessful even in the absence of indiscriminate data retention legislation. The clearance rate for cybercrime in Germany, for example, is at 58.6% and above average even without IP data retention. It fell when data retention legislation was enacted in 2009.

In the EU I observe a dangerous cycle in which national governments use all sorts of tricks to keep illegal mass surveillance going. In doing so, they disrespect rulings of the highest courts. The rule of law in the EU and the fundamental rights of citizens suffer from the surveillance greed of governments and law enforcement agencies. The EU Commission is standing idly by. The persistent violation of fundamental rights, circumvention of case-law, pressuring of judges and ignorance of facts is an attack on the rule of law we need to stop. The EU Commission now finally needs to do its job and start enforcing the landmark rulings, instead of plotting to bring back data retention.”

Twisting EU rulings into mass surveillance

The Working Party meeting was preceded by several decisions of the EU Court of Justice declaring indiscriminate retention of citizens’ communications data to be unlawful (in October 2022, the SpaceNet (C-793/19) and Telekom (C-794/19) cases and the Advocate General’s Opinion in the La Quadrature du Net and others case (C-470/21), and in September 2022, the VD (C-339/20) and SR (C-397/20) cases). Exceptions to the ban on blanket mass surveillance are only allowed under strict conditions.

However, the Belgian government had adopted a new law in 2022, which it presented at the Working Party meeting. The law represents a new generation of data retention legislation (discussion on media.ccc.de) which, formally, pretend to meet the requirements of the EU court, but in practice and de facto, continue the blanket mass retention annulled by the Courts. Similar to Belgium, the majority of EU member states, including Ireland (thegist.ie), France (Patrick Breyer)

and Denmark (itpol.dk), are pushing this policy of maximum surveillance instead of working on measured and targeted solutions. For example, the governments of the Netherlands and Bulgaria have stressed that, in their view, the general and indiscriminate retention of communications data of all citizens “is the least intrusive measure.” The consequence of this policy is a crisis of the Rule of Law in the European Union as a result of continued non-compliance with rulings of the highest EU Court.

ePrivacy: Governments want “general basis” for mass surveillance

In the Council documents, the French government calls for an exemption from the

scope of the ePrivacy Regulation in the name of national security, especially for the work of intelligence services, which would allow for blanket retention even in the absence of a present or forseeable threat to national security.

The currently negotiated ePrivacy Regulation is to replace the 2002 Directive in the future and protect citizens from data collection, tracking and surveillance. (Background information, positions of the Commission, the Council and the Parliament, as well as the possibility to comment on it at patrick-breyer.de).

France wants a “general basis” for data retention to be introduced in the ePrivacy Regulation, which would later serve as a legal framework for laws on mass surveillance of the entire population throughout the EU or in individual EU member states. The governments of Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands support this plan. The Parliament of the European Union, however, rejects this proposal. There are alternatives, for example with the Quick Freeze concept, meaning a immediate storage order upon given cause, which interferes less with fundamental rights. Austria already uses the procedure, and Germany’s Federal Minister of Justice Marco Buschmann wants tointroduce it.

Dispute: EU-wide definition of “serious crime”

In the Council session, the Commission of the European Union reported on the draft European Media Freedom Act, which is intended to regulate “the independence of the media”, “the cooperation of regulatory and supervisory bodies”, “state advertising” and “the rights of media providers” in the future. The governments of Spain, France, Bulgaria, Belgium and Italy were very concerned that the draft law contains a definition of “serious crime” in Article 2. In his Opinion on a pending judgment on an action brought by the French NGO (C-470/21) La Quadrature du Net, Advocate General Szpunur writes: “The concept of ‘serious crime’ must, in my view, be interpreted autonomously. It must not depend on the views of the individual Member States (…)” (see also edri.org). The French government, in particular, wants to “vigorously oppose (…) this request.”

What would that mean?

A possible definition of “serious crime” in the European Media Freedom Act would have to be be negotiated. Whether and for what purpose it would be necessary would also have to be discussed by the EU Parliament. If it were to be adopted with the law, it would not directly applicable to the subject of data retention. From the point of view of the individual EU member states, the definition would cover more, fewer or at least different offences than those provided for in the respective national law. This could be one reason why Paris rejects an EU-wide definition. With regard to the issue of data retention, there is a risk that the Commission could use such definition to table a new proposal for EU-wide mass surveillance. For such a definition would settle one of several points of contention between governments. On the other hand, some governments may find the proposed definition too narrow.

Spyware in journalism and the media

Article 4 of the draft European Media Freedom Act deals with criminal investigations and surveillance. More specifically, it deals with the question of the protection of journalists’ sources and the use of spyware in journalism. According to the protocol, the Commission of the European Union favours the use of such software and argues that the protection of journalists’ sources is maintained as long as it is “case-based” surveillance.